Pros and cons of releasing music directly via a distributor

What are the pros and cons of releasing a track directly through a distributor, without a label? What are the pitfalls of this process?

Vlad Zabolotsky

What we’re talking about

First, let me explain a little bit for those who don’t know. The concept of a “release,” or digital release of music, means making that music available for listening on streaming services and DJ stores. The biggest ones are Spotify and Beatport.

The difficulty is that, unlike regular services like YouTube or Soundcloud, where anyone can create an account and upload music, streaming services and DJ stores don’t work that way.

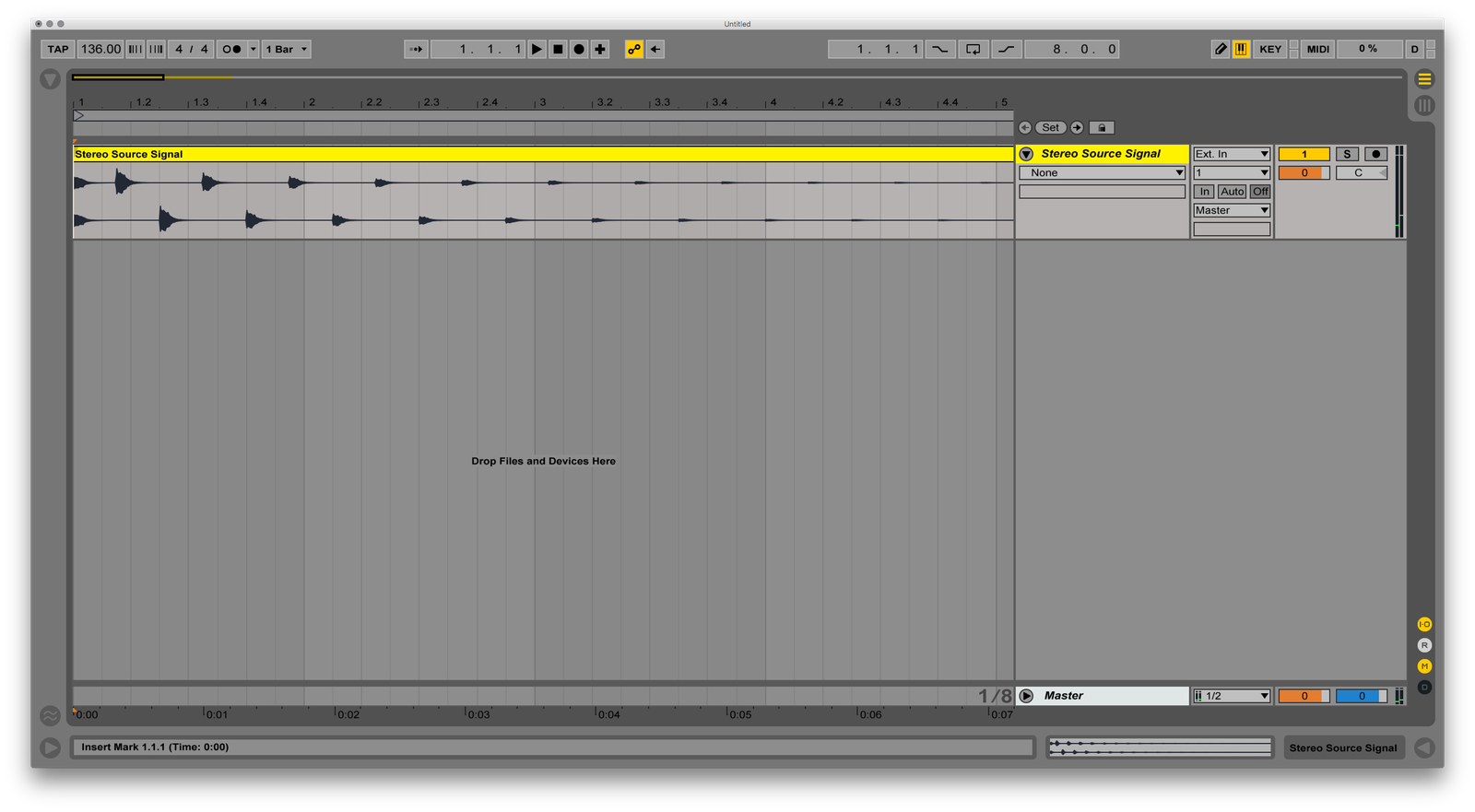

Spotify and Beatport only accept music through special intermediary services — distributors. When music is traditionally released through labels, it is the labels that take care of all the distribution work. Like this:

producer → label → distributor → services and stores

However, what Vlad is asking about is the release of music directly, that is, without the label’s involvement. Like so:

producer →

label →distributor → services and stores

That’s what I’m going to talk about.

Vlad, I’ll tell you right away that I personally didn’t release music directly through distributors. All my releases are signed on the labels, so I didn’t deal with distributors. What I do know on this subject is my general knowledge of the music industry, so take it with a grain of salt.

Why release music on your own

I see three main reasons why someone might want to release music on their own, without labels:

Timing control. With labels it’s usually like this: you send them a demo, and wait. You wait a week, two weeks, sometimes three. Then the label says: “Sorry, your track doesn’t work for us.” You send it to another label, you wait again. If you’re lucky, they accept the track, and then you wait again – for the release date. Some labels have dozens of releases in the pipeline, so sometimes you have to wait for your release for half a year or more. With self-releases, you don’t have this problem – you release as much as you want, whenever you want.

How to send a demo to a record label

Financial control. All the labels I know have a rather complicated, non-transparent, and slow reporting system. As a rule, the sales report comes either quarterly or semiannually, reflecting the previous reporting period. That said, some labels put a minimum threshold on royalty transfers of $100 to simplify accounting, meaning they withhold anything below that amount for themselves, and thus aspiring producers may not see any income for years. To be fair, sales and streaming really don’t bring in much, so it’s not the labels’ fault here. Anyway, by releasing music on your own, you see all your pennies earned and can withdraw them at any time.

Read also the truth about music sales and how much I’ve earned on the album sales

Creative freedom. Usually labels release music in a certain style, concept, and sound – it’s called a format. But sometimes they follow their own format so literally that they release tracks that are almost no different from each other. They say they are looking for originality, but in fact, they accept only the same-sounding tracks. The independent release of your own music allows you not to adjust to any format and make whatever you like.

Now I suggest we look at the specifics of distributor work.

Without a label, you can release whatever you want, whenever you want, and have 100% income from it

Cost

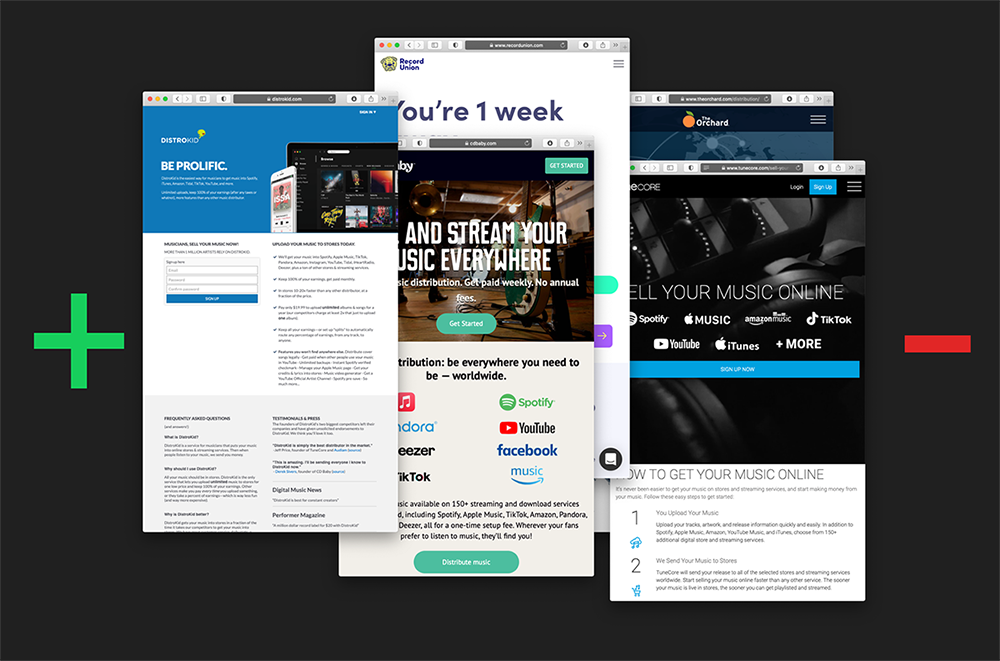

First, I think it’s important to understand what distributors are like and what their financial models are. Two of the most famous and popular ones are DistroKid and CD Baby; Spotify also recommends them.

Spotify: recommended distributors

These distributors have two fundamentally different payment models:

Subscription. DistroKid charges $20 a year for an unlimited number of releases. For that amount, you can have a release every week like Stan Kolev, but the key here is “per year”: if you don’t renew your subscription after your last paid period ends, all your music will be pulled off from the streaming services. In fact, if you choose a distributor with a subscription, you’ll basically be committed to paying every year for the rest of your life. DistroKid doesn’t take a commission, which means that 100% of your income goes to you.

It’s also worth noting that $20 a year is the minimum basic version with a limited set of features. For example, if you want to choose the exact future date of your release, that costs $36 a year.

One-time. CD Baby charges $10 for a single and $30 for an album, but only once for life. They take an additional 9% commission from the income, which leaves you with 91%.

CD Baby also has advanced versions which cost $30 for a single and $70 for an album respectively. The main difference between the regular and the “pro” versions is the publishing administration included in the price, we’ll talk about that below.

You should also have in mind the mastering and cover artworks cost, which in the case of self-release you also have to do yourself: either with your own money or with your own time.

For a self-release, you have to pay with your money and your time

Publishing

The main functions of a distributor are to put music on streaming platforms and then collect royalties from them, i.e. income. But income from music can come not only in this form, but also in other, less obvious ways: from the use of music in videos, from playback on Internet radio stations, and so on.

There are three main types of royalties: mechanical, synchronization, and public performance. I’ll write more about it someday

Now, by default, almost all distributors don’t collect these kinds of royalties. For example, some vlogger used your track in his video, and that video got millions of views. If you don’t worry about it beforehand, you won’t get anything out of that million views using your track, even though you could.

For example, DistroKid doesn’t collect royalties from anywhere except the platforms where it delivers music. The exception is YouTube: for an extra $5 per single and $15 per album per year, plus a 20% commission on revenue from YouTube.

CD Baby has a royalty fee collection included in the “pro” versions I talked about above. If your tracks get played on radio stations, clubs, or anywhere else, CD Baby will collect royalties to you as the author.

Those who work with DistroKid and other similar distributors usually have to use separate royalty collection services. For example, one such service is Songtrust. It costs $100 for a one-time registration, and then takes a 15% commission on the royalties collected.

Platforms

Every distributor has a list of platforms they deliver music to. As a rule, they all work with major streaming services like Spotify, Apple Music, Tidal, Deezer, and others.

So, all such distributors don’t deliver music to Beatport, because you have to have a label to be placed on Beatport. For example, DistroKid technically does it, but your music ends up on their label page, where all the music they’ve distributed that way is mixed up, which isn’t great in my opinion. The only exception I’m aware of is the distributor called Record Union: for $60 a year, it will deliver music to many platforms, including Beatport, though publishing administration is not included.

Some producers create their own labels with the sole role of putting their own music on Beatport, but that’s another story.

To release directly or not

Everything I wrote above is distributor features that are important to consider. But whether they are pros or cons depends solely on your goals, plan, and strategy.

For example, some people can’t imagine releasing music without being on Beatport, while others care only about streaming services and don’t care about Beatport. Or someone releases a single a year, so it’s okay to pay $30 for distribution through CD Baby, and someone releases a single every few weeks, so DistroKid might be more suitable for them.

Whether or not to release music directly depends solely on your personal goals, plan, and strategy

Personally, I think that whatever distributor you choose, an independent release, unlike a label, won’t give you the most important thing, which is your name’s affiliation with the brand. It’s like a quality mark that others say, “Oh, that producer’s from Anjuna!” Well, or Drumcode, Armada, Toolroom, you name it — any credible label in their genre. When your name is associated with a label like that, it gives you extra value, credibility, and an audience, which in turn can help to open up new possibilities.

What’s more important to you is up to you.